A visual guide to React Mental models

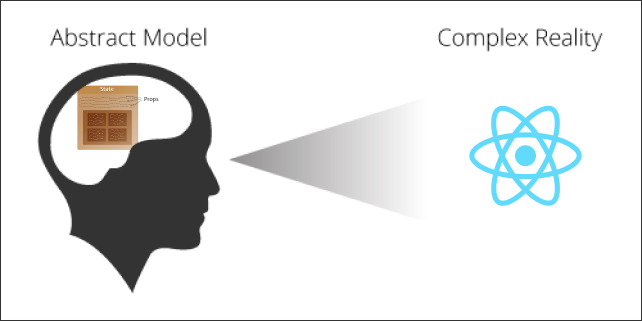

I’ve learned that the biggest difference between someone that has mastered a language, framework or tool and someone who hasn’t lies in the mental models they use. One person will have a clear and advanced one and the other will not.

By having a good mental model you can intuitively understand complex problems and devise solutions much faster than if you had to find a solution with a step-by-step process.

Whether you’ve been working with React for years or are just starting, having a useful mental model is, in my opinion, the fastest way to feel confident working with it.

In this article, I will explain those mental models that help me solve problems and tame complexity.

- This is the first part of a three part series.

- Read the

second part here, covering

useState,useEffectand a component’s lifecycles.

What’s a mental model?

A mental model is how we imagine a system to work. We create one by understanding different parts of the system and its connections, and it’s important because it helps us make sense of the world and helps us solve problems.

A good example of a mental model is the internet: it’s a complex system with many interconnected parts, but think about the way you imagine it to work. I imagine it as many computers connected through many big servers, with many middlemen redirecting where each piece of information is stored.

That’s an incomplete mental model but it’s good enough that I can work with it to solve problems and improve it if I ever need to, and that’s the gist of it: Mental models are meant to help us solve problems and understand the world.

Why are mental models important?

When I started building websites in 2014 I had a hard time understanding how it all worked. Building my blog with WordPress was easy, but I had no idea about hosting, servers, DNS, certificates, and much more.

As I read articles and tried stuff out (and broke my server config more than once) I started to grasp the system, to get glimpses into how it all worked, until eventually it “clicked” and I felt comfortable working with it. My mind had built a mental model around this system that I could use to work with it.

If someone had explained it by transferring their mental model to me, I would’ve understood it much faster. Here I’ll explain (and show) the mental models I use with React. It will help you understand React better and make you a better developer.

React Mental Models

React helps us build complex, interactive UIs more easily than ever before. It also encourages us to write code in a certain way, guiding us to create apps that are simpler to navigate and understand.

React itself is a mental model with a simple idea at its core: encapsulate portions of your app that rely on similar logic and UI and React will make sure that portion is always kept up to date.

Whether you’ve been working with React for years or are just starting, having a clear mental model is the best way to feel confident working with it. So for me to transfer my mental models to you I’ll start from first-principles and build on top of them.

It’s functions all the way down

Let’s start by modeling the basic building blocks of JavaScript and React: functions.

- A React component is just a function

- Components containing other components are functions calling other functions

- Props are the function’s arguments

This is hidden away by JSX, the markup language React uses. Strip away JSX and React is a bunch of functions calling one another. JSX is in itself an applied mental model that makes using React simpler and more intuitive.

Let’s look at each part individually.

A component is a function that returns JSX

React is used with JSX—JavaScript XML—a way to write what seems as HTML with all of JavaScript’s power. JSX offers a great applied mental model for using nested functions in a way that feels intuitive.

Let’s ignore class components and focus on the far more common functional components. A functional component is a function that behaves exactly like any other JavaScript function. React components always return JSX which is then executed and turned into HTML.

This is what simple JSX looks like:

const Li = props => <li {...props}>{props.children}</li>;

export const RickRoll = () => (

<div>

<div className='wrapper'>

<ul>

<Li color={'red'}>Never give you up</Li>

</ul>

</div>

</div>

);Which compiled into pure JavaScript by Babel:

const Li = props => React.createElement('li', props, props.children);

export const RickRoll = () =>

React.createElement(

'div',

null,

React.createElement(

'div',

{

className: 'wrapper',

},

React.createElement(

'ul',

null,

React.createElement(

Li,

{

color: 'red',

},

'Never give you up',

),

),

),

);If you find this code difficult to follow you’re not alone, and you will understand why the React team decided to use JSX instead.

Now, notice how each component is a function calling another function, and each

new component is the third argument for the React.createElement function.

Whenever you write a component, it’s useful to keep in mind that it’s a normal

JavaScript function.

An important feature of React is that a component can have many children but

only one parent. I found this a confusing until I realized it’s the same logic

HTML has, where each element must be inside other elements, and can have many

children. You can notice this in the code above, where there’s only one parent

div containing all the children.

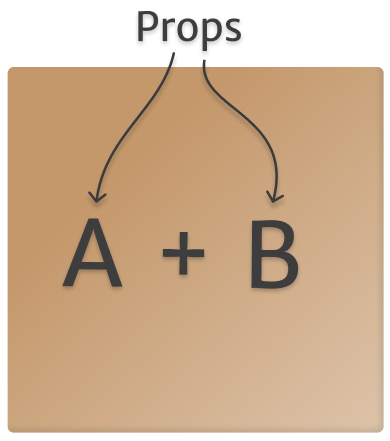

component’s props are the same as a function’s arguments

When using a function we can use arguments to share information with that

function. For React components we call these arguments props (funny story, I

didn’t realize props is short for properties for a long time).

Under the hood, props behave exactly like function arguments, the differences

are that we interact with them through the nicer interface of JSX, and that

React gives extra functionality to props such as children.

Creating a mental model around functions

Using this knowledge let’s craft a mental model to intuitively understand functions!

When I think about a function I imagine it as a box, and that box will do something whenever it’s called. It could return a value or not:

function sum(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

console.log(sum(10, 20)); // 30

function logSum(a, b) {

console.log(a + b); // 30

}Since a component is a fancy function, that makes a component a box as well,

with props as the ingredients the box needs to create the output.

When a component is executed it will run whatever logic it has, if any, and evaluate its JSX. Any tags will become HTML and any component will be executed, and the process is repeated until reaching the last component in the chain of children.

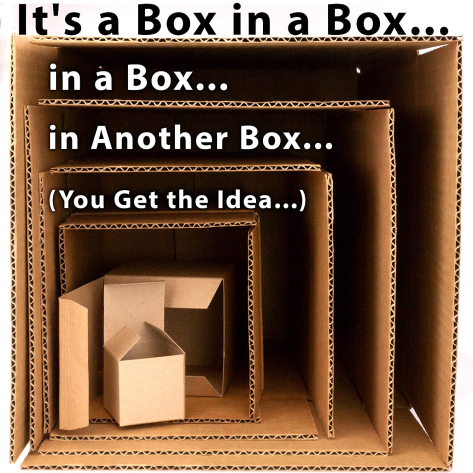

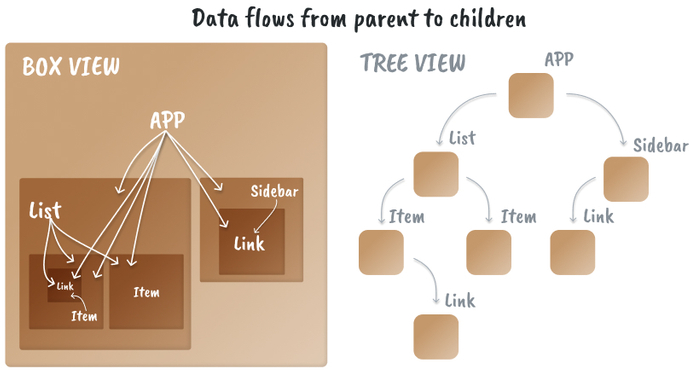

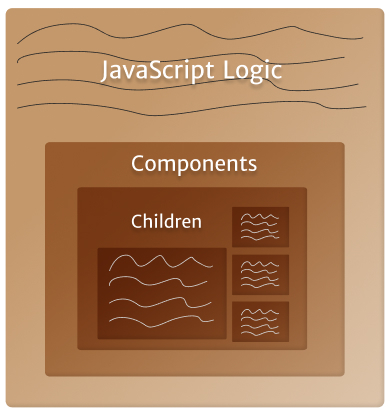

Since a component can have many children but only one parent, I imagine multiple components as a set of boxes, one inside another. Each box must be contained within a bigger box and can have many smaller boxes inside.

But the mental model of a box representing a component is not complete without understanding how it can interact with other boxes.

How To Think About Closures

Closures are a core concept in JavaScript. They enable complex functionality in the language, they’re super important to understand to have a good mental model around React.

They’re also one of the features newcomers struggle with the most, so instead of explaining the technicalities I’ll demonstrate the mental model I have around closures.

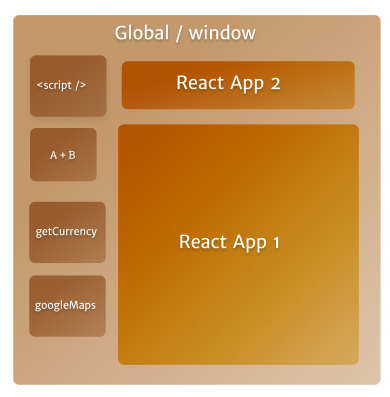

The basic description of a closure is that it’s a function. I imagine it as a box that keeps what’s inside of it from spilling out, while allowing the things outside of it from entering, like a semi-permeable box. But spilling out where?

While the closure itself is a box, any closure will be inside bigger boxes, with the outermost box being the Window object.

But what is a closure?

A closure is a feature of JavaScript functions. If you’re using a function, you’re using a closure.

As I’ve mentioned, a function is a box and that makes a closure a box too. Considering that each function can contain many others inside of it, then the closure is the ability of a function to use the information outside of it, while keeping the information it has inside from “spilling out”, or being used by the outer function.

Speaking in terms of my mental model: I imagine the functions as boxes within boxes, and each smaller box can see the information of the outer box, or parent, but the big box cannot see the smaller one’s information. That’s as simple and accurate an explanation of closures as I can make.

Closures are important because they can be exploited to create some powerful mechanics and React takes full advantage of this.

Closures in React

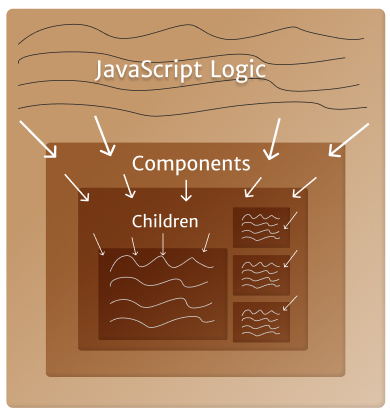

Each React component is also a closure. Within components, you can only pass props down from parent to child and the parent cannot access what’s inside the child, this is an intended feature to make our app’s data flow simpler to trace. To find where data comes from, we usually need to go up the tree to find which parent is sending it down.

A great example of closures in React is updating a parent’s state through a child component. You’ve probably done this without realizing you were messing around with closures.

To start, we know the parent can’t access the child’s information directly, but

the child can access the parent’s. So we send down that info from parent to

child through props. In this case, the information takes the shape of a

function that updates the parent’s state.

const Parent = () => {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<div>

The count is {count}

<div>

<ChildButtons onClick={setCount} count={count} />

</div>

</div>

);

};

const ChildButtons = props => (

<div>

<button onClick={() => props.onClick(props.count + 1)}>

Increase count

</button>

<button onClick={() => props.onClick(props.count - 1)}>

Decrease count

</button>

</div>

);When an onClick happens in a button, that will execute the function received

from props props.onClick, and update the value using props.count.

The insight here lies in the way we’re updating a parent’s state through a

child, in this case, the props.onClick function. The reason this works is that

the function was declared within the Parent component’s scope, within its

closure, so it will have access to the parent’s information. Once that function

is called in a child, it still lives in the same closure.

This can be hard to grasp, so the way I imagine it is as a “tunnel” between closures. Each has its own scope, but we can create a one-way communication tunnel that connects both.

Once we understand how closures affect our components, we can take the next big step: React state.

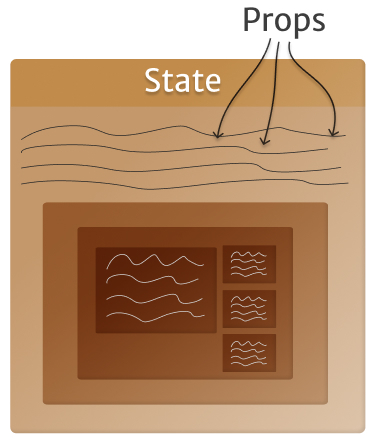

Fitting React’s State Into Our Mental Model

React’s philosophy is simple: it handles when and how to render elements, and developers control what to render. State is our tool to decide that what.

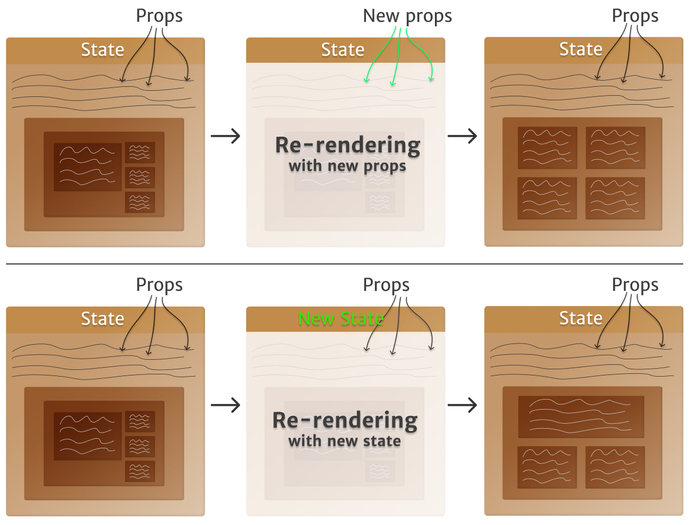

When state changes, its component renders and therefore re-executes all the code within. We do this to show new, updated information to the user.

In my mental model, state is like a special property inside the box. It’s independent of everything else that happens within it. It will get a default value on the first render and always be up to date with the latest value.

Each variable and function is created on every render, which means their values

are also brand new. Even if a variable’s value never changes, it is recalculated

and reassigned every time. That’s not the case with state, it only changes when

there’s a request for it to change via a set state event.

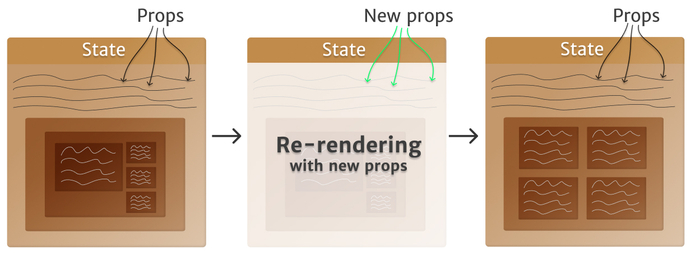

State follows a simple rule: Whenever it changes it will re-render the component and its children. Props follow the same logic, if a prop changes, the component will re-render, however, we can control state by modifying it, props are more static and usually change as a reaction to a state change.

The Rendering Mental Model: understanding React’s magic

I consider rendering to be React’s most confusing part because a lot of things happen during rendering that sometimes aren’t obvious by looking at the code. That’s why having a clear mental model helps.

The way I imagine rendering with my imaginary boxes is two-fold: the first render brings the box into existence, that’s when the state is initialized. The second part is when it re-renders, that’s the box being recycled, most of it is brand new but some important elements of it remain namely state.

On every render, everything inside a component is created, including variables and functions, that’s why we can have variables storing a calculation’s results, since they will be recalculated on every render. It’s also why functions are not reliable as values, due to their reference (the function’s value, per se) being different every render.

const Thumbnail = props => (

<div>

{props.withIcon && <AmazingIcon />}

<img src={props.imgUrl} alt={props.alt} />

</div>

);The above will give a different result depending on the props the component receives. The reason React must re-render on every prop change is that it wants to keep the user up to date with the latest information.

However, the state doesn’t change on re-renders, its value is maintained. That’s why the box is “recycled” instead of created brand new every time. Internally, React is keeping track of each box and making sure its state is always consistent. That’s how React knows when to update a component.

By imagining a box being recycled I can understand what’s going on inside of it. For simple components, it’s easy to grasp, but the more complex a component becomes, the more props it receives, the more state it maintains, the more useful a clear mental model becomes.

A complete React mental model: Putting it all together.

Now that I’ve explained all the different parts of the puzzle separately, let’s put it all together. Here’s the complete mental model I use for React components, directly translated from how I imagine them into words.

I imagine a React component as a box that contains all of its information within its walls, including its children, which are more boxes.

And like a box in the real world, it can have other boxes inside of it and these boxes can, in turn, contain more boxes. That way each box/component must have a single parent, and a parent can have many children.

The boxes are semi-permeable, meaning they never leak anything to the outside but can use information from the outside as if it belonged to them. I imagine like this to represent how closures work in JavaScript.

In React the way to share information between components is called props, the

same idea applies to function and then it’s called arguments, they both work

in the same way but with a different syntax.

Within components, information can only travel down from parents to children.

In other words, children can access their parent’s data and state, but not the

other way around, and the way we share that information is through props.

I imagine this directional sharing of information as boxes within boxes. With the inner-most box being able to absorb the parent’s data.

The box must first be created though, and this happens on render, where the

default value is given to state and just like with functions, all the code

within the component is executed. In my mental model, this is equivalent to the

box being created.

Subsequent renders, or re-renders, execute all the code in the component

again, recalculating variables, recreating functions, and so on. Everything

except for state is brand new on each render. State’s value is maintained

across renders is updated only through a set method.

In my mental model, I see re-rendering as recycling the box since most of it is recreated, but it’s still the same box due to React keeping track of the component’s state.

When a box is recycled all the boxes within it, its children, are also recycled. This can happen because the component’s state was modified or a prop changed.

Remember that a state or prop changing means the information the user sees is outdated, and React always wants to keep the UI updated so it re-renders the component that must show the new data.

By using these mental models I feel confident when working with React. They help me visualize what can be a maze of code into a comprehensive mental map. It also demystifies React and brings it to a level I’m much more comfortable with.

React is not that complex once you start understanding the core principles behind it and create some ways to imagine how your code works.

I hope this article was useful to you and it was as enjoyable to read as it was to write! I realized that I understand React intuitively and putting that understanding into words was challenging.

Want to learn more React through visual mental models?

Check out part 2,

covering useState, useEffect and a component’s lifecycles. It has even more

great illustrations than this one!

I’m planning a whole series of visual guides. Subscribing to my newsletter is the best way to know when they’re out. I only email for new, high-quality articles.